Lonely Old Men

The Agony Column for March 18, 2002

Commentary by Rick Kleffel

Reading is a lonely affair. The reader is silent, focused on the

pages of the book in front of him, aloof to the world about him. As

the real world fades, it's natural to think that the people around

the reader are less than real, less alive than those with whom one

shares the pages. Conversely, when the reader pops back into the

world around them, the utter reality of those they considered more

real than real is once again up for grabs. It's no surprise then,

that the ghost story is one of the oldest forms of story told. Once

we enter the realm of fiction, we're all lonely old men.

Ghost stories in particular seem to capture the feeling of being

alone with the pages. As the population ages, splinters, as families

drift apart, as children grow up and move away, those who were once

in our faces every day move to our memories every day, then slowly

give up that lodging as well. They may or may not be alive, yet we

drink to absent friends. Preserved by pictures, by video, loved and

once-loved ones enter a state where the difference between being

absent but alive and absent through death is difficult to

discern.

As the writers in our population age, so their thoughts too turn

to absent friends. Common wisdom might tell us that women have

cornered the market on writing that reveals deep emotional ties and

loss, but in fact it's men who have who hold the majority share on

ghost stories. Men tell one another ghost stories; it's an ancient

sign of friendship between men. Men don't do friendship nearly as

easily, nearly as well as women. Friendships between men involve a

bizarre combination of competition, cooperation, insult and one

upsmanship. When the friends go away, for whatever reason, all we're

left with are ghosts.

Perhaps the publishers are more canny than we think, perhaps the

writers are tuned to the same melancholy country music station, but

whatever the cause, there's been a positive surfeit of excellent

ghost stories haunting the bookshelves of late. If they all tell the

same story, then it's a story that needs to be told. Whether it's

told by Dan Simmons at a breakneck pace in 'A Winter Haunting', or

repeatedly, in one hundred different ways, nearly one hundred years

ago by Montague Rhodes James in 'A Pleasing Terror', or luxuriantly

by Steve Duffy and Ian Rodwell in 'The Five Quarters' or simply, by

Magnus Mills in 'Three to See the King', it's something all men sense

but few wish to face. All men are lonely old men.

|

|

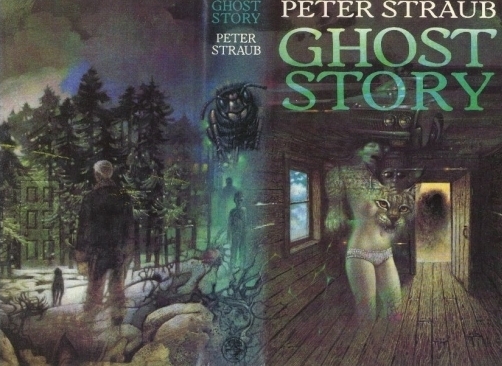

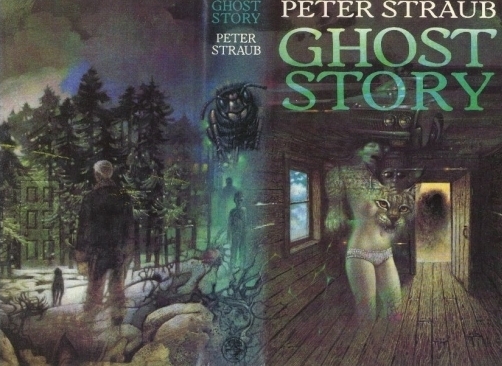

Tom Adams' beautiful gatefold cover for the UK edition

Peter Straub's 'Ghost Story' was available as a 22" by 27"

poster from the publishe, signed by artist and author. The

novel launched the horror genre into a popular and literary

spotlight in the 1980's.

|

Before we caught up in the 21st century version of ghost stories,

it's helpful to look back on the most recent progenitor of these

works, Peter Straub's 'Ghost Story'. Back in 1979, Straub did

something many would have thought impossible. He combined the

literary, deeply moving tale of four men telling stories with the

page-turning power of a supernatural thriller. He did it seamlessly,

without effort, and produced one of the greats of this or any other

century. 'Ghost Story' introduces the reader to The Chowder Society,

four old men with a dark secret who get together to tell one another

ghost stories. The story they won't tell is the one they lived

through, so long ago. Straub imbues the stories with a real sense of

regret, of loss, and of toe-curling, page turning terror. He writes

meta-fiction and stories within stories as if these had never been

invented, as if he had unearthed the literary devices with a hand

spade somewhere in the dirt in his backyard while looking for the

body of a deceased loved one. It's literally a whirlwind of

astonishing writing. It succeeded both commercially and critically,

and launched the horror genre into the 1980's with a power and a

mission that it had never before achieved. It was the story of four

lonely old men, telling one another stories. As we've done for

ages.

|

|

Dan Simmons' 'A Winter Haunting' is both a

page-turning tale of terror and a dense, multi-layered

literary Moebius strip.

|

It's not surprising that a man whose career started as Straub hit

his first peak should decide to enter the haunted, lonesome world of

lost men. Dan Simmons has managed to write in just about every genre

that he can find and to do so as if he always belonged there, as if

he'd lived and read and written in that world his entire life. Back

in 1991, he published 'Summer of Night', which is not a ghost story.

It's a coming-of-age-in-a-world-of-horror tale, boys banding together

to fight something beyond their understanding. Now, 11 years later,

Simmons has returned to that old group of friends, now separated by

time, circumstance and death. In 'A

Winter Haunting', Dale Stewart, one of the boys touched by

something back in the 'Summer of Night', has turned himself into a

lonely old man before his time. In his forties, Dale has left behind

his family and friends after a supremely selfish and stupid affair

with a student at the college where he teaches. He decides to take

some time off, to return to scene of his old crimes, to go back to

Elm Haven. He moves into the house of the character we dearly loved

in 'Summer of Night', whose life was cruelly taken by the author.

There, he does what lonely old men do these days. He sits in front of

the computer screen and types, creates a false version of his past to

paint over old pains. Simmons perfectly captures the young edge of

the lonely old man. Dale is haunted not so much by the Jamesian

ghosts of Jolly Corner, but by his own failures and the

transgressions of the recent past. He reaches out to his distant

past, and something within him, something that is within us all

answers.

But Simmons does something quite unlike your traditional ghost

story here as well. He writes a page-turning, pulse pounding novel of

suspense that keeps you up at night wondering what will happen next.

Subtext is often in your face, then buried quietly in a snowdrift. He

excavates the archetypes and marches them by the window, where they

leave footprints. And he comes up with that one single, unique,

disturbing image that sticks in your brain like burr. It is the ghost

that haunts the reader, long after the book is closed. Ghost stories

are about lonely old men, and lonely old men are scared.

|

|

Montague Rhodes James first perfected the archetype of

the "lonely old man" school of ghost stories. He's haunted

many a man since.

|

The lonely old man pictured in the frontispiece of 'A

Pleasing Terror' is Montague Rhodes James, best known as M. R.

James. He's haunted a lot of us, and this compilation from Ash Tree

Press is going to haunt a lot of people as well. That would be the

people who think about buying it but decide not to. I've mentioned

this compilation before, but in light of Simmons' novels and others,

it bears re-examination. That's because M. R. James is the

quintessential ghost teller of the lonely old man ghost story. He is

that lonely old man. The stories in here should need no introduction

to all but the most casual reader of ghost stories. The presentation

here is as stellar as the stories contained within. Richly

illustrated in a variety of traditional 'ghost story' styles, 'A

Pleasing Terror' is a masterwork of creation, compilation,

scholarship and publishing excellence.

|

|

Steve Duffy and Ian Rodwell introduce the reader to a

drinking bunch of buddies, old in the 21st century, who

reflect on the ghosts they've seen in the 20th century.

|

The one thing, the only thing that could improve 'A Pleasing

Terror' would be the non-ghostly resurrection of M. R. James, or

rather people possessed of the talents and sensibilities of M. R.

James, but driven by their own individual spark of creativity and

brilliance. Not surprisingly, it's Ash Tree Press who has found Steve

Duffy and Ian Rodwell and published 'The

Five Quarters'. The book title is the name of the group of lonely

old men who get together for a good round of drinking and seem to

always end up telling one another ghost stories. If you're thinking

of The Chowder Society, you're not alone. But 'The Five Quarters' is

a very different work, from either M. R. James, or Peter Straub,

though it resurrects the ghosts of their ghosts. 'The Five Quarters'

consists of five stories that grow progressively longer, culminating

in a final tale that is told by all five participants. Each of the

five stories allows the protagonist in the story to establish a

voice. Each of the tellers is a lonely old man, who has so much time

on his hands that he can spend it looking into matters best left

unseen. What Duffy and Rodwell do supremely well is to take the

archetypal ghost story and update it into the 21st century. They

refer back to events in the 1960's and 1980's instead of the 1860's

and 1880's, but they do so with the same wistful regret that M. R.

James did at the turn of the last century. They excavate the

universal sentiment behind these stories and do so at a length which

gives them time to luxuriate in their own fine prose. When the time

for the final tale comes, it is a whirlwind of activity, yet calm and

purposefully laid out. Duffy and Rodwell have supped from the same

table as James and Straub, but their tales are their own.

|

|

Magnus Mills speaks with the voice of a lonely man to

whom the real world is but a ghost in 'Three to See the

King'.

|

From the first paragraph of Magnus Mills' 'Three

to See the King', we know that we're in for a tale told by the

same lonely voice that graces the archetypal ghost story. But Mills

has something seriously different up his sleeve. The 'ghost' so to

speak in his novel is the world as we know it. With complete

confidence and utter aplomb, he lets his narrator lead the reader

into a world where lonely men live in tin houses on a vast plain,

separated by one another by the vast gulf of stultified friendship.

Not knowing how to be friends, they instead collide with one another

like particles in a physics experiment. Mills introduces a woman to

the environment and the entire landscape is tilted, then men collide

until they meet another man who might even be more than a ghost of

himself. But the lonely man triumphs, the lonely man haunts and

outlives humanity. He lets it pass him by. Mills' voice in this novel

has the perfect pitch of a narrator in a ghost story, and his barren

environment might well be the moors of his own England. Religious

metaphor shines through the story like a blazing light hidden behind

a closed portal. Mills' solitary narrator, alone again by choice, by

habit, because he's just a lonely man who likes being alone is like

the undead spirit who chooses to ignore the light. Transfixed by the

beauty of his own loneliness, Mills narrator would rather haunt the

present then join the future.

In the end, all the tales told by the lonely men, all the books

written by the lonely men, exist to comfort the other lonely men --

to let them know that they're not alone in their loneliness. Each of

these novels or collections of stories is simply a Moebius strip, a

one-way, one-sided journey back to the beginning. And of course, one

need not be either a man, old or even lonely to partake of the

feelings of lonely old men. There's a core of that feeling in every

reader, every time a new book is opened. The story is starting.

Prepare to be haunted.