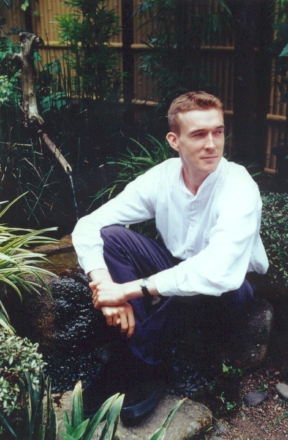

Secret Architectures:

A Conversation With David Mitchell

The Agony Column for May 16, 2005

Conducted by Nazalee Raja

We discussed his published works, his writing techniques, and also his forthcoming novel, 'Black Swan Green'. NR: 'Ghostwritten' was your first published book. Was it your first attempt at a novel?' DM: It was my second attempt at a novel. I'd written one in Japan, before 'Ghostwritten'. It was a horrible, pretentious job, a big mess of a novel. It went on far, far, far too long. I hadn't distinguished between writing something because it was good and writing something simply because I could write it. NR: 'Ghostwritten' is made up of inter-linked short stories. How do you ensure that different sections fit together to be perceived as a novel instead of a collection of short stories? DM: You have a main theme in 'Ghostwritten'. It is causality. You make each of the different voices look at that theme from a different view. Even though the stories are very different, the reader soon picks up that it's the same mountain peak that's being climbed up different paths, on different faces, each of which increases your knowledge of the same theme mountain. Another way: have them bang through the walls of each other's worlds occasionally. It happens in 'Ghostwritten' by actions. There's one action in each of the stories that makes the succeeding story possible. That links the stories. It gives the reader the sense of there being a macro plot between the covers, over and above the micro plot between the beginnings and endings of the chapters. NR: Tell us about the autobiographies you write to increase your knowledge of your characters. DM: Sure. If it's a major character, you get a page in your note book and you write in their voice about the other characters in the novel and about any of the themes. There are a relatively small number of abstract relationships between the characters and things like sexuality, work, death, aging, money, danger and language. A character is a matrix of relationships between themselves and these things. This is true in life as well. If you get your relationship with money wrong at one extreme, then you're a workaholic miser. If you get it wrong at the other extreme then you are a spendthrift. When I write a major character, I try to verbalise in my own words the character's relationship with the key abstracts. It will complicate matters where I see things that a character won't know. These things I put in brackets on the page, and it's these things which leap out at you when you finish the page. They form the foundations stones of the key scenes. Stories fail because I haven't fleshed out the characters enough, and I'm using a cloak of invisibility rather than an x-ray. The autobiographical method is particularly useful when your story is in a hole. To get it out, go back to autobiography and you will see all sorts of things. Fiction, I think, is all about people. In a way, it's very, very simple. You have someone that the reader is empathising with and doesn't want bad things to happen to, and then you either make bad things happen or let the reader think bad things are going to happen to them, and constantly make the reader ask 'Is he going to be ok?', 'Is she going to be alright?' When people talk about being glued to a book, each time I think that is what is happening. NR: You have talked in the past about an 'artist's inner architecture'. What do you mean by this and how do you make this work for you in your novels?

'Ghostwritten' is about causality and each of the stories is a sort of essay by example on a different theory or angle of causality. In the first story, things happen because people abdicate their wills to the guru. In the second story in 'Ghostwritten', the key things happen because of love. In the third story, about the corrupt Hong Kong stockbroker, everything is happening because of greed. In the fourth story, set in a tea shack in China, everything happens because of historical forces. The rest of the stories in 'Ghostwritten' go on like that. In 'number9dream', the secret architecture is that each of the different sections are in a 'state of the mind' form. The first section is about daydreams, about the power of fantasy through daydreams. The second is about memory, written through partly through flashbacks. The third is image, written though the experience of playing video games, moving images. The fourth is kind of a nightmare and is about nightmares. In 'Cloud Atlas', the secret architecture is about different methods of transmitting a narrative. The first one, the Adam Ewing section, is about a journal, written in the form of a journal. The second is about transmitting a narratives through letters, and is written in the form of letters. The third is actually about the novel, and is written using the format of a cheap airport thriller. The fourth is memoir, the fifth is interview. The sixth is vernacular, the spoken method, the most ancient and probably the last of all human means of transmitting a narrative. This is what I mean by secret architecture. The reader doesn't always know that this is happening, but nonetheless, it is. I think of it in terms of when I walk into a cathedral I don't really understand the mechanics of the force that is keeping tons and tons of stone up for hundreds of years up above my head, but nonetheless the cathedral stays up.

DM: Cliché is something you must always be on your guard against. Writers need built in cliché detectors that go off when what you're writing looks like something you saw on a not very good Hollywood film. Yes, it is a problem, but problems are thing you should aim at, not avoid, because there always are ways around problems. Always, always! The more unique the problem the more original the path you have to take to get around the problem. There is gold in them there clichés, and there is gold in them there plausible things! NR: When you sit down to compose a novel, do you outline each portion of the novel? DM: I do both. I outline one given internal whole, one chunk of the novel, and I also outline the sequence of chunks that make up the whole novel. It gives you a place to start and a direction to move in. Then, even if you want to leave your original plan in a subsequent re-write to do something completely different, or you disassemble the structure and re-assemble it, if you have an initial outline to move through or sequence of scenes you want to write, it stops you staring at a blank page or blank laptop. NR: The Timothy Cavendish character from 'Ghostwritten' also appears in 'Cloud Atlas', and the Mongolian character, Subaatar, appears in both 'Ghostwritten' and 'number9dream'. Can we expect this feature in forthcoming books? DM: Yes. Tim Cavendish, who has got a big role in 'Cloud Atlas', is a minor character in the London section of 'Ghostwritten'. In one of the 13 chapters of 'Black Swan Green', a major character is a woman in her sixties called Eva van Outryve de Crommmelynck, now an old lady. She's the daughter of Madam Crommmelynck, wife of Vyvyan Ayrs, who the composer Robert Frobisher, went to stay with in 'Cloud Atlas'. In the same section, there's a very minor character, called Gwendolin Bendincks, who appears in the old folks home in the Timothy Cavendish section, about fifteen, twenty years before Timothy Cavendish meets her. She's a waspish vicars' wife in Black Swan Green. I do it for two reasons. One, it's enormous fun to get people back from literary limbo and to give them more pages, to think of them as actors and actresses who are hectoring screenwriters for work. The other reason is simply that the more time you have considered a character the more concrete they appear on the page, even if they don't have that much to say.

DM: I don't think I do prepare. You just finish one and start the next. You do a bit of autobiographical sketching, and of course you do research. I don't meditate, or get in character like an actor going on stage, or anything like that. I just get in my hut and get back to it. NR: You have almost completed your fourth novel, 'Black Swan Green'. Can you give us a hint what it is about? Does it have a linear format? DM: It's about 13 months in the life of a 13 year old boy. It's set in a small, narrow village in South Worcestershire that the narrative only leaves twice. It's 1982, in the cold war, and the year of the Falklands war. Each chapter is one short story that I've tried to write as an independent short story. The narrator is bright, a little bit like the narrator in my second novel. He's a lot more articulate inside his head than outside. I'm also using the book to look at speech impediments and stammering. Each of the short story chapters takes place in a month in one of the thirteen months of the novel, so it moves through the seasons. Each of them has its own sub-plot and its own theme, but the cast in continually being re-cycled, rather like I've done in Ghostwritten but to a much greater degree. Background characters in one story can have major significance 8 months later. I'm trying to study the eternal black hole in age between being a boy and being a teenager. I'm allergic to the title 'Coming of Age Novel'. There's always a kind of a journey at character level in fiction, and if that journey happens to occur to a fifteen year old, then people say, 'Aha, it's a Coming of Age Novel'. It's the best thing I've written. I'm quite confident of that. NR: Will you begin your next novel as soon as you finish 'Black Swan Green'? DM: Oh yes! I love writing. I absolutely love it. It's wonderful. It doesn't seem like work. Writing bends time. There's no sense of needing a holiday or needing a rest. Writing is rest and stimulation and everything else. It's not always easy and it's exhausting too, but if it's your vocation, then you know what it's like. NR: That you very much for taking the time to do this. DM: You're very, very welcome. |