|

|

|

This Just In...News from the Agony Column

|

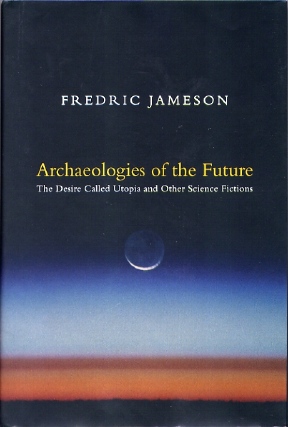

12-02-05: Frederic Jameson 'Archaeologies of the Future' |

||||||

Utopia,

Science Fiction and Change

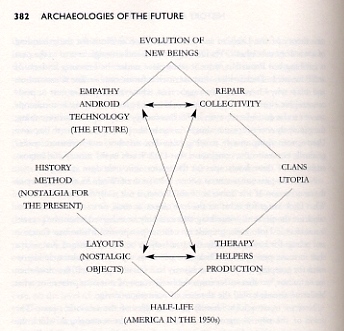

But it's not the only idea, nor should it be. It's been a long time since I visited my list of difficult reading, but dont take that to mean I've stopped reading difficult books. The latest and perhaps the greatest bit of difficult reading to come way is 'Archaeologies of the Future: the Desire Called Utopia and Other Science Fictions' (Verso ; October 20, 2005 ; $35) by Frederic Jameson. When I suggest that 'Archaeologies of the Future' is difficult, I mean that it will prove difficult for just about any serious reader to put this book down. It's positively mesmerizing. Jameson is a serious critic, and he's awesomely well read, both in and out of genre fiction. But let's leap past that for a moment and emphasize something unexpected in this work. That is, this book will cause just about every single reader of this column to stop and drool as Jameson unfurls trenchant, mind boggling -- in the best science fictional sense of the word -- observations about every single one of our favorite writers on every single page of this book. It's utterly impossible to open up 'Archaeologies of the Future' without stumbling across deep thoughts about a writer you've read and loved. Never fails, every time you touch the book. Mind you, this is not slick bestseller prose. This is a serious academic examination of the role of utopia in genre fiction. Here's a sample of what you'll get to read, from the essay in Part II titled "World Reduction in Le Guin": "It would certainly be possible to see the Gethenian environment as extrapolating one of our own earth seasons, in an extrapolation developed according to its own inner logic and pushed to its ultimate consequences -- as for example, when Pohl and Kornbluth project out onto a planetary scale, in The Space Merchants, huckstering trends already becoming visible in the nascent consumer society of 1952; or when Brunner in The Sheep Look Up, catastrophically speeds up the environmental pollution already under way. Yet this strikes me as being the least interesting thing about Le Guin's experiment, which is based on a principle of systematic exclusion, a kind of surgical excision of empirical reality, something like a process of ontological attenuation in which the sheer teeming multiplicity of what exists, of what we call reality, is deliberately thinned and weeded out through an operation of radical abstraction and simplification which I will henceforth call world reduction."

First off, let me re-emphasize that every page in this book contains a mention and analysis of one of the essential works of literature that SF readers either are familiar with because they've read them or familiar with because they've heard about them from folks like me ad nauseum. It's a non-stop parade of SF's greatest hits, from Gwyneth Jones to Robert Heinlein, from Ursula K. Le Guin to A. E. Van Vogt. You cannot escape from the great in this book, and Jameson is no doubt no snob; witness a serious an in-depth examination of 'The Space of Science Fiction: Narrative Structure in Van Vogt'. This is a man who deeply -- black hole deeply -- understands science fiction, and why it is so utterly important. 'Archaeologies of the Future' is set forth in two distinct parts. Part One, titled 'The Desire Called Utopia,' is divided into chapters, and runs some 233 pages. Typical chapter titles included 'The Utopian Enclave', 'The Unknowability Thesis', 'The Alien Body' and 'Synthesis, Irony, Neutralization and the Moment of Truth'. The thrust here is a bit more general, a complex look at the fiction of perfection. Part Two, titled 'As Far As Thought Can Reach,' is something of a reference for Part One. The focus of the essays here is on specific works and specific writers. It consists of twelve essays, which include the above-mentioned piece on Van Vogt, two essays on Philip K. Dick, the essay on Le Guin, and "If I Can Find One Good City, I Will Spare the Man": Realism and Utopia in Kim Stanley Robinson's Mars Trilogy". And more! Phew! 'Archaeologies of the Future' is in fact an academic tome, but it's an academic tome that is utterly gripping. It's Important with a capital "I", but more than that, it's important because Jameson can write a sentence that literally forces readers to think; not simply because what Jameson is saying is thoughtful and original, but also because it's compelling. Jameson writes well enough to make you want to know what he knows. He'll inspire you to work through his theses. If you want the world and you want it now, then you're going to need some documentation to run it. Here it is. Have at it. Rule The World. |

|

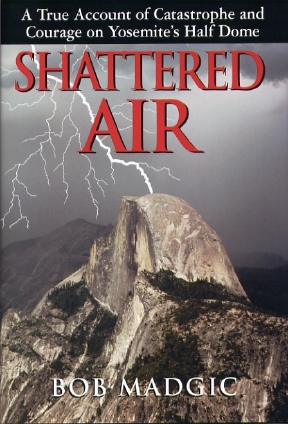

12-01-05: Bob Madgic's 'Shattered Air' |

|||

Electric

Yosemite

I suppose I should set the scene before I start talking about the presentation and the book. It had been raining most of the day; weather was far from ideal. I picked my son up from his after-school job at 6:30 PM, then drove out to pick up his friend. We stopped on the way to the talk -- which started at 7:30, picked up some fast food for the kids, then headed over to the bookstore. Capitola Book Café is located in a sort of shopping center with a grocery store, a drug store, a movie theater and a home supplies store. The parking lot was surprisingly crowded for 7:15 on a rainy Tuesday night. But when we arrived in the store, we found that it was already packed. They have chairs for about 40 people, but I have to guess that there were twice that number there. It was standing room only, with an attentive crowd, waiting to hear Madgic discuss his book. Now readers may not think me the type to have lots of bestsellers hanging about on my shelves, and they'd be right, but one hardcover bestseller I bought purely on reviews and publicity was Jon Krakauer's 'Into Thin Air', about an ill-fated attempt to climb Everest. Madgic's book is a tale of similar hubris, and his presentation was informative and gripping. If he's showing up in your neck of the woods, I'd suggest you hie yourself down to the bookstore and catch the show; and even if he isnt, the book might be well worth your time, especially if you enjoyed 'Into Thin Air' (I did) or if youre interested in lightning strikes (I am; it's a Fortean interest that gets filed under "em" in my Fortean folder for "electro-magnetic" related events). The story told in the book, Madgic told us before the slide show, falls into three parts and parties. The first party involved was a group of two rock climbers, one of them a son of one of Madgic's former students. These two guys were themselves students at the time, 18 year-old kids rock climbing up the face of Half-Dome with practically no equipment. Between them, they had a single glove. On the Friday before the main events, these two guys were on the face in the rain and in a thunderstorm. Apparently this is a VERY BAD IDEA. While they were on the face, Half-Dome was struck repeatedly, and they were shocked repeatedly by the current, which was conducted across the wet granite. Madgic told us that a) over the years, lightning causes more weather-related injuries than any other form of extreme weather other than floods, around 80 injuries (including death) per year in the US alone and b) most lightning related injuries are not the result of a direct strike, but rather, the result of an indirect strike. Fortunately for these kids, they were just shocked and suffered no permanent injury. Lightning kills, Madgic told us, by cardiac arrest and not always on the spot. The other injury caused by lightning is, as Madgic put it, "It scrambles your software." Brain damage, which is one of my phobias. How about you? Lightning in fact killed someone in King's Canyon the next day, Saturday. Madgic had hiked to the spot where it happened and showed us in his slide show. I guess the typical advice given for those caught in a lightning storm is "take shelter", but alas, this is a two-edged sword, as seems obvious. Hiding under a tree, or even, as this hiker had, under a rock is no guarantee of safety. And this fatality occurred in a totally counter-intuitive place for a lightning strike, as we could see in Madgic's photo. It was a sort of small cave between two huge rocks on a trail in the middle of a forest. It just was not where youd expect to find a death by lightning; the guy was surrounded by trees. Sheltered -- and killed. The main event took place on Sunday, July 27, 1985. A party of nine hikers left, and five decided to continue up to the top even when it was clear that there would be a thunderstorm. Now, Madgic sets this all up very nicely in his show, talking about the folks who left, particularly the leader, Tom Rice. Madgic showed slides of the 45-foot cliff that Rice liked to have his co-climbers jump off of before climbing; yes, you did land in a 15-foot deep pool of water at the bottom, hitting the surface at 36 MPH. He also showed slides of the Diving Board, a ledge at the top that Rice liked to stand on backwards, on one foot. Though I've lived my life in California, I've not yet made it to Yosemite, and one of the interesting aspects of this talk was the look at the history and geology and geography of Yosemite that Madgic gave. Lots of great slides of the park and the places the climbers found themselves. As he told the story of what happened that day and night, the large audience was silent, still and riveted. It was fascinating, especially to me -- and I presume many others -- who had read 'Into Thin Air'. Madgic's tale involved many of the aspects of that work, and was just as gripping. But the events that Madgic covered were far more human-sized than the grander scale of 'Into Thin Air'. You could identify with the people who went on the trip much more closely than you could the millionaire hikers who went 'Into Thin Air'. I know lots of people who have hiked up Half-Dome, and I dont know anyone who has climbed up Everest. But the same forces that doomed the Everest expedition -- hubris and a hard-headedness about the dangers one faces in natural settings --were at work here, on a smaller mountain. I guess the lesson that people are stupid is not surprising. But the fact that it can happen here, is alas, always surprising. And so once again, I find myself with an unexpectedly good book to hand, and an object lesson in why you should on occasion leave the house at night, if it involves going to a bookstore, that is. Madgic's book is certainly worth checking out if you find such tales of interest, and if youre lucky enough to have him bring his slide show into town, make a date. Even the teenagers enjoyed it. They both found it compelling enough to stand still and stay quiet through the whole presentation. It's even worth braving in the rain, the thunder and lightning. So long as he's not giving the talk on Half-Dome. |

|

Scott Lynch Tells 'The Lies of Locke Lamora' |

|||

"Add

Colors to the Chameleon"

Even before the massive success of the Lord of the Rings movies, the massive success of the Lord of the Rings books had tainted and polluted what was once -- and still is, one finds with a bit of effort - a very diverse genre. These days, "fantasy" seems to translate roughly to: LOTR ripoff. Boob rube from the boonies gets a thingie that helps him overthrow a despot. That, at least is the "high concept" version of LOTR and pretty much of the fantasy genre. Now you can do some interesting things within this definition, but, not to put too fine a point on it: why bother? Tolkien did it already, and there are plenty of others out there who are doing it well at every level, from complex thrillers to boy's-own-adventures. There are so many out there that it's created a sort of gravity well, a black hole that few can escape from. Of course, in such an environment, those who are different can thrive. Look at Terry Pratchett, who either lampoons or eschews the fantasy conventions to the delight of legions of readers. Those same legions are likely to flock to Scott Lynch when 'The Lies of Locke Lamora' (Victor Gollancz / Orion Books ; July 20, 2005 ; £17.99 / Bantam / Del Rey / Spectra / Random House ; June 27. 2006; $23) is published mid-year next year. Expect big things readers; banner ads, maybe even standees, blurbs from the gods. Or if not Zeus, maybe George R. R. Martin. First and foremost, let me suggest that readers make an effort to pick up the UK version, and here's why. This book was first bought in the UK, and brought to fruition by the careful editorial hands of Simon Spanton. He sent me an excerpt long ago, which I loved, but didn't want to bring up until the end product was at least in sight. So no matter what date the book is actually published, to my mind, the true first edition is the VG edition. And you can always do the two-book tango. Buy the UK version, wrap it up and admire it and take the US version out to lunch with you. Or buy two US versions, one for archival purposes and one to take to lunch. You can even buy the second one in a chain bookstore, as this will send a message to the publisher that you like these sort of things to be published. Good books, that is. As with all prose artifacts (books), the final proof is in the actual writing. But even on the "high concept" level, Lynch distinguishes himself. Yes, we do have Camorr, a world of fantasy here, with swords, ships and tavern-keepers. But it's built upon the ruins of something perhaps more science fictional, so even the background gets a bit of invention. But the high concept here is quite simple. 'The Lies of Locke Lamora' is a "fantasy" 'Ocean's 11'. Now that's something even a movie studio executive could understand! Locke Lamora is bad man, with an alias. As the Thorn of Camorr, he's a legend. As Locke, well, he's smarter than the average bear and a good deal wittier. Only not so witty as to avoid getting caught between a rock (Capa Barsavi, this novel's "Thief Lord") and a hard place (The Grey King, this novel's Darth Vader). Can wit triumph over might? What do you think? Well, what I think is: "Why hasnt this been done before?" Yes, Fritz Lieber's Fafhrd and the Grey Mouser novels have a bit of this, as do the Pratchett Discworld novels. But as I said above, the final proof is in the actual writing. And Lynch delivers an appallingly enjoyable shtick that is itself witty enough to make you believe his character's wit as well. There's a formula to this book, but its a good one, and the tale is well-told. So sleep on this readers, for a good six months. Then wake up to the standees, the cover blurbs and ignore them. Focus on the words. They're pretty damn entertaining. Otherwise, why bother? |

|

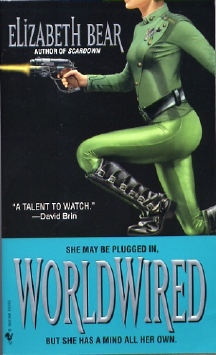

11-29-05: Elizabeth Bear is 'Worldwired' |

|||||||||

A

Serious Series Novel

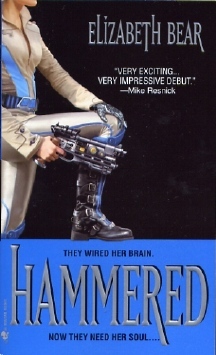

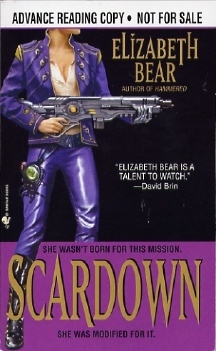

And yes, all that attention is helpful. Bear has been on the radar of discerning readers for quite some time, with her many excellent short-story contributions to Interzone and other SF venues. Like most authors headed up the food chain, we expected that eventually she'd "graduate" from short story writer to novelist. What we didn't expect was that she'd manage to sort of re-invent the novel and re-invigorate the science fiction series when she did. Her first novel, 'Hammered', introduced readers to Jenny Casey, a delightful jack-booted UN enforcer pounding the gritty streets of Toronto in a near future every bit as bleak as the present. Drugs, unemployment, and petty wars were running rampant and Casey's case rapidly escalated from a gritty mean-streets cop thriller into a space-based conspiracy and confrontation with something other. Released late in 2004, it was quickly followed up in mid-2005 by 'Scardown'. With the release of 'Worldwired' less than a year after the first "novel" in the "series", it's clear we're seeing something rather more interesting than a writer who has created an interesting character and given her a series of adventures. 'Hammered', 'Scardown' and 'Worldwired' are no less and much more than a single novel in three novels.

At this point, it might help to talk a bit about the two kinds of series that writers can offer readers. One is "The Continuing adventures of..." In this form of the series, each novel offers the beginning and end of a single story. It's a form much loved and well-used by mystery writers. In each novel, the protagonist solves a crime. While the characters can and should develop as the novels progress, each novel in itself stands alone. From Arthur Conan Doyle to Laurie King, from Robert B. Parker to Bill Pronzini, the mystery genre has thrived on this form. Science fiction writers have as well, often wrapping their speculations around a mystery plot. Richard Morgan comes quickly to mind, as does Jasper Fforde, and Isaac Asimov with his Elijah Bailey and Daneel Olivaw books. Even fantasy writer Terry Pratchett likes to pound a mean street in novels like 'Night Watch' and 'Thud!' The other form of a series is that in which a longer story is broken up into single-novel fragments. I'm currently enjoying Kage Baker's Company novels. I started at the beginning with 'The Garden of Iden' and I'm currently wrapped up in 'Sky Coyote'. I know, I'm way behind but what a great ride this is! Here, each story stands on its own, but they're all clearly part of a larger arc, which I and many others are dying to find out about. 'Lord of the Rings' is the fantasy trilogy icon of a story in three novels and -- enough said!

While many of us finished the novel in a year, I was curious if Bear did so as well. She told me that, "I actually didn't. The funny story is that this thing's been in my head for over a decade. I started Hammered in 1994 and failed utterly to get it to work, so I trunked it and came back in 2002. I wrote that one in summer of 2002, Scardown in winter of 2003, and Worldwired in 2004. So, a little bit less than 24 months for the whole set. My editor, Anne Groell, said it might be the fastest three-book contract she's ever seen, since the first two were written by the time they series sold in 2003. Total elapsed time from contract to publication of the third book, almost exactly two years." I also had to ask her if my intuition -- that the three novels were sort of one -- was correct, and she replied that, "It's all one book--all one story--although there are thematic and focal length shifts between the three parts, and I tried to break it where the shifts and the big cast changes happen." Now this is not totally new and it's not totally unique. Kim Stanley Robinson is currently in the midst of a three-novel novel, which started with 'Forty Signs of Rain', was followed up by 'Fifty Degrees below' and will be completed, he recently told me, next fall -- he does know how it is going to end. And I recently covered Peter F. Hamilton's 'Commonwealth Saga', split into two ginormous 900 page-plus novels, though Hamilton does leave you with a bit of a cliffhanger at the end of 'Pandora's Star'. These forms exist in the mystery world as well. George Pelecanos wrote a novel in three parts with his Derek Strange and Terry Quinn novels, 'Right as Rain', 'Hell to Pay' and 'Soul Circus'. Pelecanos' take on the tripartite novel was a bit looser than Bear's, but no less a single story, nicely divided. In fact, between Bear, Pelecanos and Robinson, we're seeing a really interesting development in the form of fiction itself. Writers are thinking about readers in the long term. That is, writers are presuming that readers will be very closely with them, following a single story over multiple volumes. That may not seem like any great revelation, but it implies that writers and publishers alike believe that readers are willing and able to sustain their attention over a rather long period of time. And it most importantly implies that everyone understands that WE LIKE READING. Yep, we do like reading, authors and publishers. Keep getting us great novels, whether theyre published in one or more volumes, and we'll come back. Trust your writers and trust your readers. Is there a new generation of readers out there? Sure, so long as publishers trust that the folks buying books are in fact reading them. We're not hoping they'll be turned into movies or TV shows. We're waiting for the next one, and the next. Bring it on! |

|

11-28-05: 'His Majesty's Dragon' by Naomi Novik |

||||||||||||

On the Wings of a Massive Marketing Campaign

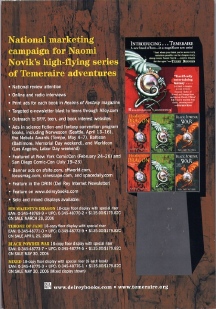

They were among the first books to really attract me to science fiction, and I can still see myself standing in the bookstore in Covina looking out the window then down at these books. It's one of those touchstone reading memories that keeps the practice of reading alive for me. So I'm always interested in dragon books, and not least because they guarantee a good monster, often an intelligent monster that can function as an interesting character. That's the ideal, as it offers a good author the chance to provide a highly entertaining scaffold upon which to build imaginative prose and story riffs. Of course, the results can vary. Sometimes you get a tract house and sometime you get a Taj Mahal. Del Rey Books is apparently counting on Naomi Novik to land on the spectacular side with 'His Majesty's Dragon' (Del Rey / Random House ; March 28, 2005 ; $7.50). This will be followed by 'Throne of Jade' (April 25, 2005) and 'Black Powder War' (May 30, 2005). Yes, you're hearing about them here first, but dont worry, you won't be able to miss them. This is the kind of series that gets launched with standees in the bookstore, and unless you trip over the display, you'll not have a hard time finding them.

No, what makes these books interesting to me and my readers is Novik's entertainingly well-designed scaffold, based on her love of two other writers; Patrick O'Brian and Jane Austen. Take all these influences, shake and bake, and you get the Temeraire series. The setup is pretty sweet. In the midst of the Napoleonic wars, the HMS Reliant captures a French frigate and seizes the cargo -- an unhatched dragon egg. Captain Will Laurence finds himself in the Aerial Corps, the master of the dragon Temeraire. He'll have to learn fast as the French are preparing their own legions to strike on British soil. Strike -- and sear. In and of itself, this is a very clever premise that offers at a minimum a chance for great adventure fiction. You can read the Stephen King blurb there, and be warned that you'll be able to recite it before long, as it will be the basis for banner ads on all the SF websites that offer you that delightful content. And if not on those websites, then on the standees in the bookstores. And yes, there's a fantasy / alternate history spin for these novels that looks rather similar to Clarke's novel. Moreover, I have to say that having another fantasy writer inspired by the prose of Jane Austen is simply a wonderful trend. Influences within the genre that are themselves outside of the genre enliven fantasy by bringing in the unexpected. We expect fire and flying and scales in a book about dragons. We dont necessarily expect witty social banter. But works informed by Jane Austen do at least suggest an interest on the part of the author in such goings-on.

Novik does her part in this equation by providing Del Rey (and herself) with not only an excellent scaffold, but some excellent writing as well. It's one thing to be inspired by Austen and O'Brian and it's another to actually write a novel that reminiscent of them. 'His Majesty's Dragon' brings to mind an altogether very different novel, R. A. MacAvoy's 'Tea With the Black Dragon'. Yes, for all the foo-foo influences, Novik has mainly capitalized on the potential for dragons to be entertaining characters. There's a sort of straightforward feel to the conversations here; the questions asked and the answers offered are the very ones that will be on the tip of the reader's tongue.

Clearly it's a profit-and-loss, bottom-line decision, but readers like myself, who'd prefer to first experience a great book in hardcover, will be able to pick up the UK version, titled 'Temeraire', from HarperCollins in January. Alas the publication schedule for the follow-ups is not as peppy as it is in the US. Or you can drop by Novik's website. But if you just can't wait, and the US versions are coming out, is that not enough of a good thing? And how can that be a bad thing? No matter what kind of thing it may be, one thing is certain: it will be a hard to miss thing. Get ready for a blast of fire, and hope you dont burn out on dragons. |