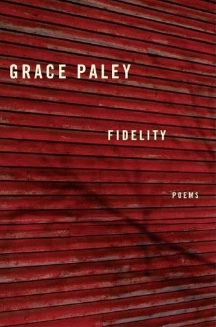

Reading Grace Paley's final poetry collection, 'Fidelity', leaves one

feeling something akin to walking through a dicey neighborhood in the

midst of urban renewal – hope and despair, the romantic and the

run-down reside side by side. On page after page, they coexist in straightforward

musings as only Paley could deliver them.

Some poems have titles, but many go untitled. Like punctuation other

than line breaks and spacing, they are just extra clutter she has no

use for. Here is a poem from the first section of the book:

Anti-Love Poem

Sometimes you don't want to love the person you love

you turn your face away from that face

whose eyes lips might make you give up anger

forget insult steal sadness of not wanting

to love turn away then turn away at breakfast

in the evening don't lift your eyes from the paper

to see that face in all its seriousness a

sweetness of concentration he holds his book

in his hand the hard-knuckled winter wood-

scarred fingers turn away that's all you can

do old as you are to save yourself from love

Surely every poet writes about love and death, death and love. In these

poems, Paley doesn't just know her time is limited in the way we all

know, abstractly, the fact of our own mortality, but knows it in a real

way that carries imminent consequences: 'Fidelity' was published posthumously

in March of this year. Paley succumbed to breast cancer in August of

2007 at the age of 84. To steal a phrase from her poem “Sisters”

“the word dead is correct/but inappropriate.”

She writes often about friends and family who are failing or already

gone in verse that is tender, unsentimental and frequently run through

with an off-handed humor: “the reproductive/ and recreational

organs /of many of my older friends/ have been declared redundant dangerous/to

the hardworking body” (from “Many”).

In one untitled piece she interrupts herself midway to pen the lines,

“In any event I am/ already old and therefore a little ashamed/

to have written this poem full/ of complaints against mortality...”

Her observations of and encounters with strangers zoom in with the same

compassionate eye she affords those close to her. Poems like “Bravery

on Tenth Street,” with the focus of a frail older couple walking

along the street, “I Met a Woman on the Plane,” about her

conversation with a mother who lost a child, and the untitled poem that

begins “the very little girl looked at her grandfather”

are all testimonials to her careful involvement with the subject matter

about which she writes. From the final poem in the aforementioned list:

“...a man she'd seen/ last week was bobbing his head and waving

his/ arms and shouting go away and stop it and go/ to hell other words

very loud no one came/...bye-bye she said she/ waved the man exhausted

softly said bye-bye.”

It feels as if Paley is determined to get it right, and, clear in her

understanding that such a thing is impossible, she plugs her ears to

the sirens of fatalism and sidles up next to the reader, elbowing her

and pointing. “Get a load of this!” her poems seem to say,

marveling with infinite curiosity at this stubbornly broken world.

News

although we would prefer to talk

and talk it into psychological the-

or the prevalence of small genocides

or the recent disease floating

toward us from another continent we

must not while she speaks her eyes

frighten us she is only one person

she tells us her terrible news we

want to leave the room we may not

we must listen in this wrong world this

is what we must do we must bear it

A long-time political activist who worked for peace, Paley never stopped

supporting causes she believed in or speaking out whether asked to or

not.

In the poem “To the Vermont Arts Council on its Fortieth Birthday,”

she is invited to speak and opens by recalling when she turned forty

herself. She continues, talking about how soon after that birthday the

country dived into the Vietnam War and she muses on what artists of

all kinds made of that. Her poem ends this way: “...another/

American war with an unknown people/ thousands of miles away luckily/

Vermont the United States and the/ Arts Council is deep in poets most/

of us with big mouths (it is said) even/ the gentlest.”

Paley is her own best adjective – a name meaning at once compassionate,

vibrant, irreverent, melancholy, someone with unerring chutspah.

If you were looking for lyric poems that roll in luxurious language

and subtle metaphor, you chose the wrong book. Paley's poetry is closer

to colloquial, rough around the edges and uninterested in the degree

of craft that would buff the hard truth out of the meaning.

True, a handful of these poems don't quite come round to poetry and

clunk off the tracks. But mostly they are charming and unexpected beauties,

like the beloved across from you at the dinner table, too engrossed

in what he or she wants to say to wipe the ketchup from the sides of

their mouth.

Sadly, we can't all have an activist New York grandmother who writes

poetry; but fortunately, we can borrow the legacy of Grace Paley..