|

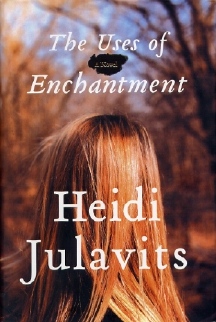

Heidi Julavits

Heidi Julavits

The Uses of Enchantment

Reviewed by: Rick Kleffel © 2006

Doubleday / Random House

US Hardcover First Edition

ISBN 0-385-51323-2

356 Pages; $23.95

Publication Date: 10-17-2006

Date Reviewed: 12-07-06

Index:

Mystery

General Fiction

Horror

Ambiguity attracts anxiety. Friedrich Nietzsche famously advised that, "If you gaze for long into an abyss, the abyss also looks into you." Heady stuff, that. Jeff Lint, the non-existent science fiction writer created by Steve Aylett suggested that, "When the abyss gazes into you, bill it." Not quite so heady, perhaps, but no less perceptive. Heidi Julavits offers readers her own version of the abyss, the smart-as-a-whip (and just as stinging) teenage kidnap victim, or perhaps runaway, Mary Veal. Julavits snaps her literary lash at a variety of targets, every one of them within the reader of 'The Uses of Enchantment'. At once subtle and snarky, 'The Uses of Enchantment' is an elegantly de-constructed psychological thriller that reads like a rocket. It's smart, fast, furious and fun, though likely to evoke feelings you might wish to forget. But disturbing is as disturbing does and that's where the ambiguity comes in, followed by that flood of anxiety.

In a sense, not much verifiably happens to the characters in 'The Uses of Enchantment'. In 1985, Mary Veal, a fairly ordinary seventeen year-old girl at Semmerling Academy, an all-girl prep school in New England, is kidnapped. Or at least, she goes missing, and returns a month later, suggesting that she's been kidnapped but is the victim of amnesia. Her mother, a frosty socialite who makes much of her Salem-witch ancestry, sends young Mary to a psychologist named Doctor Hammer. Fifteen years later, Mary, now an adult, well sort of, returns to her home town for her mother's funeral, where she mingles once again with her two sisters and her father.

Julavits spins an elegant thriller by telling this story in three inter-linked narratives, each of which is a joy to read. One narrative is unfolded in portions labeled "What Might Have Happened", told in a creepy, voyeuristic third-person omniscient voice. This describes, well, what might have happened to Mary Veal from the time of her supposed kidnapping forward. Another narrative takes place in the present of the story, in West Salem, 1999, as Mary attends her mother's funeral. These parts of the story are told in a more conventional, comedic and conversational third-person voice. Then there are the "Notes" written in the first person, of Doctor Hammer as he talks with Mary Veal after her ordeal and tries to pierce the veils of amnesia (or, perhaps, lies ) that shroud Mary's memory of what happened to her in her one-month absence.

The cast of characters in 'The Uses of Enchantment' is small and vivid when they are not overripe and blurry. Julavits plays with both poles of characterization to evoke unsettling effects within the reader. Mary Veal is our central, soul-sucking abyss, when she's not being a catty single thirty-something post-adolescent teenager. Both mystery and solution, depending on which portion of the narrative you’re reading, Mary is ever and always joy to read around. Reading around is the proper description of the reading experience of Mary's character. We see lots of borders but get to fill in the details of the countryside with our own anxieties. Paired with or against her is Doctor Hammer, an everyman psychologist who is clearly floundering in the vacuum of Mary's missing memories. Like any good man, he invents a decent story to cover his own fears and feelings. Unlike most men, he manages to put this story together and get it published, so that his eventual disgrace is assured.

To tell her story and evoke the humor and horror that are central, Julavits has created a magnificently clear set of narratives that are intricately inter-locked and cleverly deployed. You get the full-on fear of seeing Mary go missing blurred into a cat-and-mouse game in which the cat might discover that he is not the predator but instead the prey. The danger that young women experience in the presence of older men can be transformed in an instant to the danger that older men may find themselves in when they allow themselves to be alone with younger women. But as this story progresses we see both the immediate and the long-term aftereffects of what might or might not have transpired. Julavits keeps each portion of the story entertaining and grippingly short, doling out her tale in compellingly readable time-slices. The effect is to keep the reader racing through the novel, as much to find some feeling of relief from all the tension and ambiguity as to find out both what happened in the past and what will be discovered in the present.

'The Uses of Enchantment' displays a fascination with stories and storytelling because it is a story that is alarmingly well-told. It is frequently quite funny, but the laughter is always verging on hysteria as opposed to hysterical. Julavits ruthlessly lampoons the worlds of psychology, psychiatry and fiction while managing to resurrect and rebuild the reputation of no less an outcast than Sigmund Freud. She gets in some sly family-gathering humor and evokes the entire spectrum of fear, from subtle and unsettling to witch-burning, shrieking terror, though no actual witch burning takes place. Metaphorical witch-burning is clearly on tap.

Readers of 'The Uses of Enchantment' might find themselves hard-pressed to say precisely what happens in the novel, but what happens within the reader is crystal clear. Julavits' novel is always entertaining, whether it is simply touching nerves or stretching them to the breaking point. It's impressively intelligent without wearing its smarts on its sleeve. It is suffused with the invisible and obsessed with the intangible. It might be an abyss into which you may gaze at your peril, or it might be a mirror that magnifies your anxieties.

|

|